Challenging the Status Quo: Merritt Clifton on Best Friends' Influence in Animal Shelters

Examining the Impact of Advocacy and Controversy on the No-Kill Movement

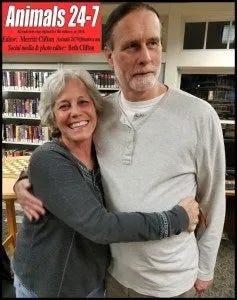

Merritt Clifton is a distinguished figure in animal welfare journalism, known for his fearless dedication to uncovering the truths that shape public opinion and policy. Since beginning his career in 1968, Clifton has focused on complex animal and habitat-related issues, using investigative journalism to provoke critical debates on topics ranging from zoonotic diseases to breed-specific legislation. As co-founder, with his wife Beth, of Animals 24-7, an independent online investigative newspaper, Clifton has become a pivotal voice in reporting on the intricate challenges facing animal shelters.

Clifton's work has been both praised and criticized for its bold approach to controversial topics. However, his commitment to exposing uncomfortable truths has earned him accolades, including the ProMED-mail Award for Excellence in Outbreak Reporting, cementing his impact on public discourse and policy. Through Animals 24-7, Clifton continues to spark meaningful conversations that push for more humane and responsible approaches to animal welfare.

As the no-kill movement faces increasing scrutiny, Clifton argues that fundamental missteps have overshadowed the movement’s original goals and hampered meaningful progress. He highlights the risks associated with an uncritical embrace of pit bull advocacy, noting that this approach not only neglects public safety concerns but also leads to a cycle of overpopulation that is detrimental to animal welfare overall.

Interview with Merritt Clifton

Ed Boks: Merritt, thank you for joining me today. You recently responded to a previous Animal Politics article with significant concerns about the direction Best Friends Animal Society took towards pit bull advocacy starting in 2005. Why do you see this as a wrong turn for the no-kill movement?

Merritt Clifton: Thank you, Ed. The shift towards pit bull advocacy by Best Friends marked a significant departure from essential strategies for achieving authentic no-kill animal control. This change actually began in 1996, when Richard Avanzino and Nathan Winograd rebranded pit bulls as “St. Francis terriers” in an attempt to rehome them. The initiative collapsed quickly after some of these dogs killed cats, underscoring the risks involved.

In 2005, Best Friends revived this effort. Instead of addressing overpopulation or public safety, they doubled down on pit bull advocacy, denying the risks associated with pit bulls. In particular, Best Friends took custody of some of the pit bulls impounded from football player/dogfighter Michael Vick in 2007 and misleadingly promoted them as “Victory” dogs, even though surprisingly few of them were ever successfully rehomed and some reportedly killed other animals at the Best Friends sanctuary. Best Friends continued to deny pit bull risk even after pit bulls killed Best Friends network volunteer Rebecca Carey, 23, of Decatur, Georgia, in August 2012, and severely injured Best Friends employee Jacqueline Bedsaul Johnson, 61, on December 4, 2017.

Pit bull advocacy shifted the Best Friends focus away from more urgent and broadly effective measures to end shelter killing.

Ed Boks: You've been a vocal critic of how the no-kill movement has prioritized pit bull advocacy. Can you elaborate on where this focus detracts from the broader mission?

Merritt Clifton: Absolutely. No-kill strategies have increasingly focused on adoption rather than addressing root causes of overpopulation. The pit bull advocacy, in particular, diverted attention from more foundational solutions like spay/neuter programs. About 30 years ago, Peter Marsh had developed his model for getting to no-kill animal control through targeted subsidized spay/neuter. He demonstrated that it worked in New Hampshire. Surplus litters were coming almost entirely from lower-income families. Wherever low-cost and free spay/neuter services were available, shelter intake rapidly dropped down to just un-handleable feral cats (ballpark of 40%), dangerous dogs (ballpark of 30%, mostly pit bulls), and lost-and-found pets, who were and are the smallest common category of intake (10% maybe), with many other reasons for intake together averaging maybe 20%.

It doesn’t take an advanced degree in math or animal behavior to realize that even if you can push all of the feral cats out the door into neuter/return programs (which succeed well if you have no community resistance), half of your remaining intake will be dangerous dogs. No matter how much you redefine dangerous dogs, you can’t have 50% of your total intake be dangerous dogs and responsibly achieve a 90% live release rate.

So instead of focusing on controlling the population through effective prevention methods, we’ve been trying to adopt our way out of the problem. This strategy doesn't address the reality of shelter demographics—like the high number of dangerous dogs that often make up a significant portion of intake.

Ed Boks: How did this focus shift priorities away from other solutions like spay/neuter.

Merritt Clifton: By emphasizing pit bull rehoming, the movement neglected the more pressing issues of population control and public safety. The immense resources poured into pit bull advocacy did little to reduce euthanasia rates across the board. Despite this focus, shelter adoptions have actually decreased, and key issues—such as expanding spay/neuter services or managing feral cat populations—remain largely unaddressed. The movement became focused on individual stories rather than systemic solutions.

Ed Boks: As we look at the current state of the movement, we will also consider the implications of new approaches being promoted by leaders in the field, like Kristen Hassen, who is currently advocating for some controversial methods in Los Angeles. But first, I recall that at the 1995 No-Kill Conference, you outlined three conditions necessary for no-kill success. Could you remind us what those were?

Merritt Clifton: Yes, the three essential conditions I outlined were: First, ensuring widespread access to free or low-cost spay/neuter services to prevent surplus births. Second, pit bulls should be sterilized out of existence due to their high involvement in fatal attacks on humans and others. Third, feral cats should be managed through neuter-and-return programs until they are no longer a visible problem in communities. These strategies are foundational to any legitimate effort at achieving no-kill status.

Ed Boks: While I don’t support sterilizing pit bulls out of existence, I do see the value of targeted spay/neuter programs, especially when we consider the animals dying in the largest numbers in our shelters are pit bulls and feral cats. If we focus on those two categories, achieving no-kill seems assured. Have organizations like Best Friends or Maddie’s Fund pursued these recommendations?

Merritt Clifton: Unfortunately, no. Both organizations have retreated from expanding spay/neuter services, focusing instead on advocacy and adoption efforts that don’t address the root causes of overpopulation or public safety concerns. This misalignment of priorities has diluted the impact of the no-kill movement and created an illusion of progress rather than actual change.

Ed Boks: What are your thoughts on the current state of the no-kill movement?

Merritt Clifton: The movement has lost sight of the core strategies needed for real, sustainable progress. Ken White, a respected voice in the humane community, predicted back in 1995 that without a disciplined approach, the no-kill movement would face severe setbacks. He was right.

Producing the ANIMALS 24-7 news website for the past 10 years plus, we have seen a lot of energy expended, but not enough focus on effective animal control strategies. In fact, we have seen dozens, perhaps hundreds, of spay/neuter organizations that began with high hopes in the early days of the no-kill movement falter and fail in recent years as the major foundations that formerly funded spay/neuter redirected funding to promote adoptions, especially pit bull adoptions. The consequences of this lack of attention and funding are apparent in today’s overcrowded shelters and persistent overpopulation issues, including in the particularly dismal explosion of mass animal hoarding cases involving shelters and shelter-less “rescues.”

Ed Boks: You bring up an interesting dynamic. Do you feel Best Friends is partially to blame for 'rescue hoarding'?

Merritt Clifton: The “rescue hoarding” problem has more than quadrupled since I first began logging cases in 1982, in terms of numbers of offending humans and organizations. It is also up more than 40-fold in terms of numbers of animals involved––and that is just counting the live animals impounded when hoarding operations are finally raided. There is no way to count the dead, but it probably amounts to a substantial share of the numbers of animals claimed as “saved” by shelters passing animals out without background checks or follow-ups, in order to get their “live release” rates up to the 90% standard that Best Friends defines as the no-kill threshold.

Ed Boks: What are your thoughts on the effectiveness of Best Friends' "embed program," which is currently being proposed in Los Angeles? Have there been any proven successes of this program in other locations?

Merritt Clifton: The "embed program" seems drawn from the U.S. military's strategy of embedding journalists with units in Afghanistan and Iraq, which reduced costs and risks while also limiting independent coverage. Similarly, embedding Best Friends personnel in animal control shelters aims to increase their control at the expense of local authority. However, this approach is unlikely to succeed because it is based on the false premise that 90% of shelter intakes are healthy or adoptable animals, which is no longer true. Shelter intakes now largely consist of feral cats, dangerous dogs, and lost pets. Even if feral cats are managed through neuter/return programs, a significant portion of intakes will still be dangerous dogs, making it unrealistic to achieve a 90% live release rate.

Ed Boks: Speaking of intakes, what are your thoughts regarding Kristen Hassen's promotion of "limited intakes" and "by-appointment surrenders"?

Merritt Clifton: The concept of "limited intakes" and "by-appointment surrenders" is akin to proposing limited response times for police and fire services, which is clearly impractical. Animal control agencies are essential public services that respond to emergencies and prevent them from occurring. Reducing intake without addressing the root causes will lead to more unvaccinated and non-sterilized animals on the streets, worsening public safety issues similar to those seen in developing countries. Historically, such approaches have resulted in mass exterminations of problematic animals by frightened citizens.

Ed Boks: Given Kristen Hassen's belief that community animals will thrive on the compassion of local residents, what do you think of this approach in terms of ensuring the well-being and safety of these homeless animals?

Merritt Clifton: Kristen Hassen's career has often left behind issues like dog attacks and lawsuits without improving outcomes for homeless animals. Her belief that animals can thrive without conventional sheltering overlooks the harsh realities faced by community animals, such as roadkill, poisoning, and predation. Effective control measures—such as managing dangerous dogs, providing accessible sterilization services, and ensuring anti-rabies vaccination—are crucial for the well-being of community animals. Countries like Turkey have shown that without these measures, even historically animal-friendly nations can face catastrophic failures in managing street animal populations.

Ed Boks: Hassen also promotes “By-Appointment Adoptions”? Has that ever worked?

Merritt Clifton: This is nothing new, although the mechanisms may differ. Decades ago many animal shelters offered adoptions during limited hours which created about the same inconvenience to the public as this proposal; it was allegedly also a way to conceal what was actually going on in the shelters.

The North Shore Animal League was the first big shelter to handle adoptions as a retail operation rather than an inconvenient interruption to mass killing. The idea caught on rapidly. Hassan seems to be trying to turn the clock back to those pre-North Shore days. And of course her approach would allow a return to high-volume undisclosed shelter killing. Could that really happen? Well, why take the chance?

Ed Boks: Given the various challenges we've discussed, where do you believe the no-kill movement should redirect its focus to regain momentum?

Merritt Clifton: Make the Best Friends Animal Sanctuary an asylum for homeless lunatics, redirect the Maddie’s Fund assets to treating drug addicts, and then refocus on spay/neuter. That’s what got us to where we could even discuss no-kill animal control as a possibility.

We also need to be concerned about preventing dog attacks, not to mention fatalities, which had the U.S. averaging under one a year from 1930 to 1960 compared to an average of 69 fatalities per year over the past three years. The average for pit bull related fatalities during that same three year period was 50 per year.

Also, we must look at expanding the effective use of neuter/return; it has reduced the national feral cat population to as low as 1.4 million, according to projections from the D.C. Feral Cat Count of 2021.

Ed Boks: Are you serious about Best Friends?

Merritt Clifton: Damned right I’m serious. But it could be said that the Best Friends Animal Society was always a sanctuary for homeless lunatics. The difference was that before 2005 they were harmless homeless lunatics.

Ed Boks: Thank you for your candor, Merritt. Your perspective certainly adds an important dimension to these ongoing discussions in animal welfare.

Conclusion

Ken White’s prediction that the no-kill movement would eventually collapse under the weight of its own contradictions may have been premature, but it highlights a crucial flaw in the current approach. The focus on live-release rates, driven by pit bull advocacy and the rebranding of dangerous dogs, has created a distorted version of no-kill that ignores fundamental safety concerns and the real solutions that could reduce shelter intake.

To truly realize the goals of the no-kill movement, we must return to the strategies that have already proven successful, like targeted spay/neuter programs that address the root of overpopulation. New Hampshire’s model, pioneered 30 years ago by Peter Marsh, offers a clear blueprint: reducing intake by providing accessible, subsidized spay/neuter services to low-income communities is the most effective way to reduce the numbers of animals entering shelters in the first place.

Moving forward, animal welfare leaders must prioritize prevention over reaction, focusing not on rehoming dangerous dogs to achieve high live-release rates, but on stopping the cycle of surplus litters. If the no-kill movement is to survive, it needs to evolve—balancing compassion with responsibility, and public safety with lifesaving. It's time for a course correction that puts real, sustainable solutions at the forefront.

Ed Boks is a former Executive Director of the New York City, Los Angeles, and Maricopa County Animal Care & Control Departments. He is available for consultations. His work has been published in the LA Times, New York Times, Newsweek, Real Clear Policy, Sentient Media, and now on Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

Recently, I was at the San Jancinto Shelter pulling a dog. A small room filled with people turning in their animals with a woman at the window asking for a chihuahua. She was told to come back in a few days after it had been fixed. She responded in aghast, "What if I want to have puppies?" I was shocked then not shocked. The community is not in alignment with the state of affairs of the plight of animals (She could have just turned around to see the turn ins). Some will never be because they don't subscribe to it, just that animals are more of a prop or tool to be used for some outcome.

Which brings this back to this article. People have to believe and hold true that animal welfare is and has a function in society. And all the attributes of that standard has performance.

It's all in the culture. It's all in the messaging. And it's all in how we ensure that performance of animal welfare, including legal enforcement, is carried out.

When I was in Las Vegas a few weeks ago, the blvd was populated by electronic billboards, sponsored by lawyers, to adopt at the shelter and ads played on the radio the same.

Ms. Hassen, as she goes by now, is propagating ideals from HAAS and seemingly carrying the ideologically brainwashing of "the message." I have reviewed her court cases, articles and results and find them immature and blatantly diverting responsibility.

When I attended several CalAnimals Seminars, one class specifically focused on leaving the animals on the streets. I objected and was told that is what is wanted. Another class proposed it was racist and DEI.

Critical thinking has deflated to follow the masses.

We need leadership that is bold and the elected officials must allow for this common sense, effective, progressive strategies back in to our shelters. This is a Titanic objective to turn the ship in that direction though a steady turn will do it... if we have a captain.

Ed thank you for the interview as it’s important to consider all voices.

After reading, I’m reminded of what Gabor Mate talks about with respect to childhood trauma. Much of the current mental illness crisis in America’s youth can be traced to unresolved trauma. You simply cannot “release” kids into the adult world without effective treatment. The results are obvious in our current culture. Much work needs to be done before dangerous dogs can simply be adopted out—regardless of breed.

Some fascinating parallels. Some kids just aren’t fit for the broader adult population—but we obviously can’t sterilize them out of existence—the work must be done to treat and educate them if they did not get that from their parents.