Police, Pets, and Public Trust: Why Are So Many Dogs Killed by Cops—and What Can Be Done?

Ask Me Anything #17 / Animal Politic with Ed Boks

The dog wasn’t charging. She was running—away from a police vehicle.

In a shaky cellphone video, a bystander yells, “They’re only scaring her more!” As the police car accelerates toward the fleeing dog, the voice rises in disbelief: “He just tried to run her over!” Then comes a final plea: “She’s not aggressive!”

Moments later, the dog disappears from view with the cruiser close behind. Then: three, maybe four gunshots. The bystander begins to cry.

The dog is dead.

A Tragedy That’s All Too Common

It happens far more often than most realize. As many as 10,000 dogs are shot by police each year—and that’s just an estimate. Most departments don’t track the numbers. In most cases, the dogs posed no real threat. Few result in discipline.

This incident happened in a quiet public park in Brookshire, Texas. No bite. No growl. No visible threat. Just another life ended, and another community left asking: Why do police keep killing our dogs?

The mother dog, as she’s become known, had no name in public records—she was "the stray mother dog." One of her puppies was later struck and killed by a passing vehicle. But her surviving puppy, Thalia (aka Lolly), is now cared for by Belle’s Buds Rescue, waiting for a chance at a loving home.

Behind every statistic is a name and a story.

Sometimes called “puppycide”, these killings occur with disturbing regularity. For communities already wary of law enforcement, watching a pet gunned down only deepens distrust—and for animal lovers, it feels like a betrayal of basic decency. There is no reliable national count—most law enforcement agencies don’t track animal deaths, so the true number is likely much higher.

These shootings don’t just take lives—they destroy trust. Families lose beloved companions. Cities face lawsuits and constitutional challenges. And communities, especially those already distrustful of police, grow even more skeptical.

The System Behind the Silence

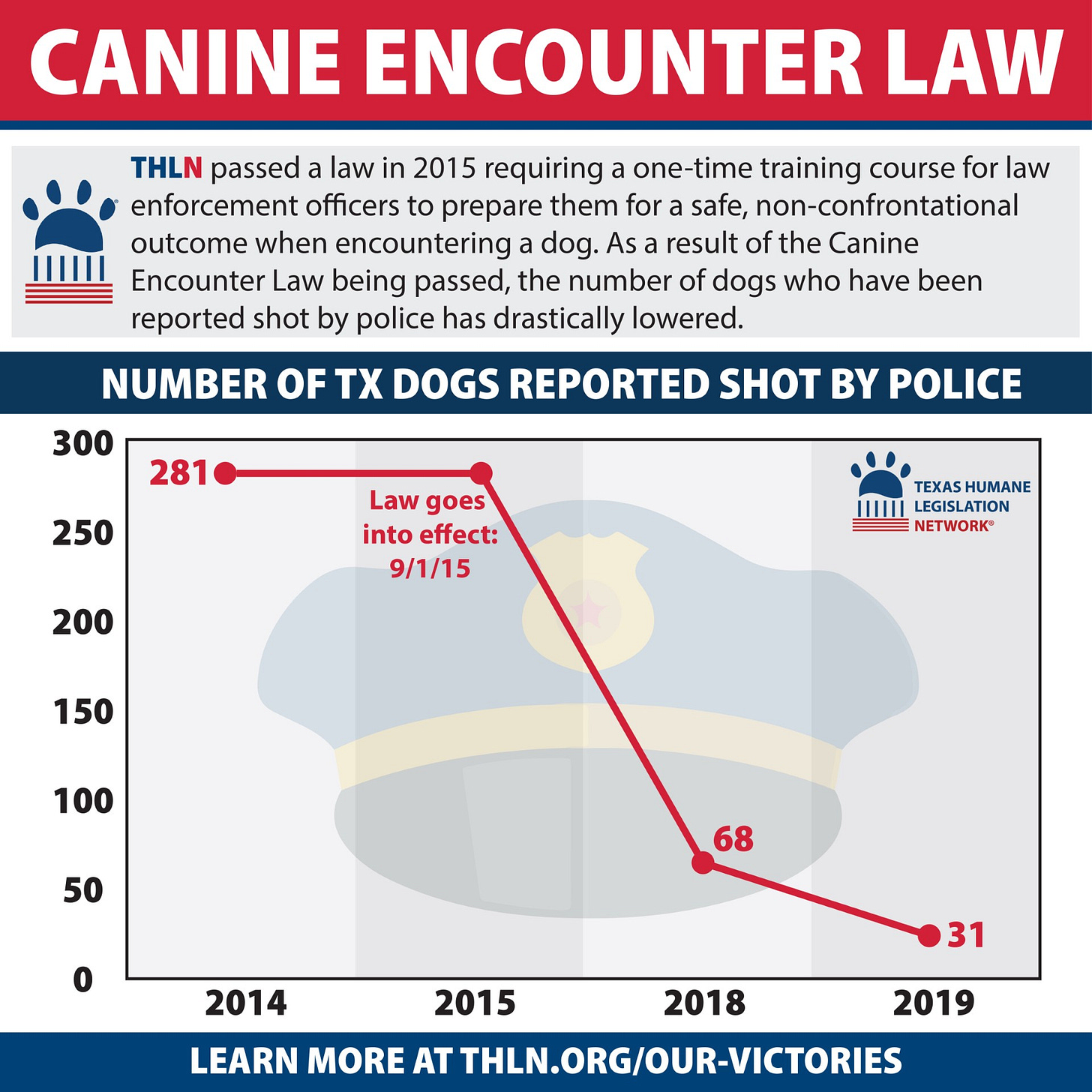

Behind the headlines lies a deeper story—of outdated practices, missed opportunities, and a growing push for reform. In response to public outcry, Texas became one of the first states to mandate canine encounter training for many law enforcement officers, aiming to prevent tragedies like Brookshire by equipping officers with the skills to handle dog encounters humanely.

The Question

Why do police so often use deadly force against dogs—and how can we stop it?

Animal Politics’ Response

Let’s start with a hard truth: most police officers receive little to no training in how to safely interact with dogs.

When officers respond to a call—adrenaline running high—and a dog approaches, barking or wagging, many don’t know how to interpret what they’re seeing. Is the tail wagging from excitement—or fear? Is the bark aggressive—or defensive? Lacking tools, time, or training, some officers default to their weapon.

Texas actually mandates a course called Canine Encounters (TCOLE #4065)—but only for some officers.

Officers in small departments like Brookshire may never have taken the course. It’s required for new cadets and officers seeking advanced certification, but many veteran officers—particularly in rural agencies—have no obligation to complete it.

So while the state has a course, the tragedy in Brookshire shows how easily it can be missed. That failure is part of a national pattern—but it’s also one that reformers are beginning to change. Across the country, a growing number of departments are investing in canine encounter training, and the results are real.

Programs like LEDET (Law Enforcement Dog Encounters Training), developed by animal behavior experts and law enforcement trainers, offer scenario-based instruction—including virtual reality simulations—that teach officers how to interpret canine body language and de-escalate encounters. These trainings reduce unnecessary shootings, build officer confidence, and save cities from costly litigation. These programs prove what Brookshire didn’t: when officers are properly trained, dogs don’t have to die.

Training That Works—When It’s Used

Texas’s own Canine Encounters course requires in-person, scenario-based skill evaluations. Officers are taught not just to read a dog’s posture and eyes—but to physically rehearse calming, non-lethal interventions. These include using body language to defuse tension, deploying treats or tools as distractions, and de-escalating before force becomes necessary.

Some departments now equip officers with dog deterrent tools like shields, bite-sticks, catch poles, and no-harm repellents—alternatives that protect both human and animal life.

The Texas curriculum outlines a clear use-of-force continuum for dog encounters: start with presence and verbal commands. If necessary, use distractions like clipboards or jackets. Only after all else fails—and only if the dog poses an immediate threat—should deadly force be considered.

Yet many officers skip these steps entirely—either because they were never trained, or because their department treats the curriculum as optional. In both cases, dogs pay the price.

The Courts Weigh In

Federal courts have repeatedly held that killing a dog without an imminent threat may constitute an unreasonable seizure under the Fourth Amendment.

In San Jose Charter of Hells Angels Motorcycle Club v. City of San Jose (2005), the Ninth Circuit ruled that officers must have probable cause to kill a dog during police operations.

In Brown v. Battle Creek Police Department (2016), the Sixth Circuit recognized that the unreasonable seizure of a companion animal by law enforcement can be unconstitutional, though it upheld the officers’ actions in that specific instance.

More recently, in Ray v. Roane (2022), the Fourth Circuit allowed a lawsuit to proceed to trial, finding that a jury should determine whether an officer’s shooting of a family dog was an unreasonable use of force under the Fourth Amendment.

The Law Is Clear—So Why Are Dogs Still Dying?

Texas officers are explicitly taught that legal justification for lethal force does not shield them from civil liability. The curriculum warns: if an officer recklessly injures or kills an animal—or worse, harms a bystander—the defense collapses. Yet in Brookshire, that legal risk was either ignored or never understood.

In other words: ignorance is no defense. Departments that fail to train their officers are exposing themselves to legal, financial, and moral liability.

What Needs to Happen

The Brookshire case is not just a tragedy—it must be a turning point. The internal investigation cleared the officer, stating he followed policy “by the book.” But that book was written before modern training, humane alternatives, or public accountability were even considered standard. If the current rules justify killing a frightened dog in a public park, then it’s time to write a new book.

The officer in Brookshire likely interpreted the dog’s behavior as a threat—rather than stress, fear, or confusion. But the state curriculum teaches officers to read subtle cues: “whale eye,” tucked tail, lowered head. These aren’t signs of aggression. They’re signs of fear. A properly trained officer would have known the difference.

If we want to stop these unnecessary killings, we need more than outrage. We need action. That means demanding:

Mandatory dog encounter training for all law enforcement officers—not just as a suggestion, but as a standard.

Transparent, public tracking of police-involved animal shootings—because what isn’t counted can’t be managed.

Investment in non-lethal tools and technologies that give officers real alternatives to pulling the trigger.

Formal partnerships between police and animal control professionals—to ensure expert guidance is available when it matters most.

Public accountability for officer training: In Texas, citizens can file a Public Information Act Request to verify whether an officer involved in a shooting has completed the required canine encounter training. This transparency is vital for building trust and ensuring humane policing.

This is not anti-police. It’s pro-safety, pro-accountability, and pro-compassion. We owe it to our communities, our officers, and the animals we call family to do better. Now is the time.

Let Brookshire be the last wake-up call we need.

Ask Me Anything

Has your dog—or your community—been affected by police violence? Share your story in the comments or email me directly. Let’s keep the pressure on.

Call your local police department.

Ask if their officers are trained in canine encounters.

If not, demand it.

The fix is simple: the training already exists, it’s inexpensive, and more than 3,000 officers in Texas have already taken it. Making it mandatory in every community is low-hanging fruit—just like seatbelt laws and body cams once were. This isn’t a radical reform. It’s common sense—and long overdue.

Ed Boks is a former Executive Director of the New York City, City of Los Angeles, and Maricopa County Animal Care & Control Departments, and a former Board Director of the National Animal Control Association. His work has been published in the LA Times, New York Times, Newsweek, Real Clear Policy, Sentient Media, and now on Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

Stay Informed

For more analysis and updates on the evolving landscape of animal welfare policy, visit Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

People love guns, they love cruelty.

Your assertion that mandatory training is low-hanging fruit is 🎯

A simple, actionable step that can save lives and strengthen communities

Excellent article!!!