San Diego Humane Society’s Community Cat Program Faces Legal Scrutiny Over the Release of Adoptable Cats

Lawsuit Challenges Controversial Practice with Potential Implications for Shelters and Community Cat Programs Nationwide

A legal battle between the Pet Assistance Foundation (PAF) and the San Diego Humane Society (SDHS) has shed light on the controversial practice of releasing friendly, adoptable cats back into the community under SDHS’s Community Cat Program (CCP). The plaintiffs, represented by attorney Bryan Pease, argue that SDHS is violating California law by releasing not only feral cats but also socialized, adoptable cats that could potentially thrive in homes. This practice, they claim, constitutes illegal animal abandonment under California Penal Code 597S.

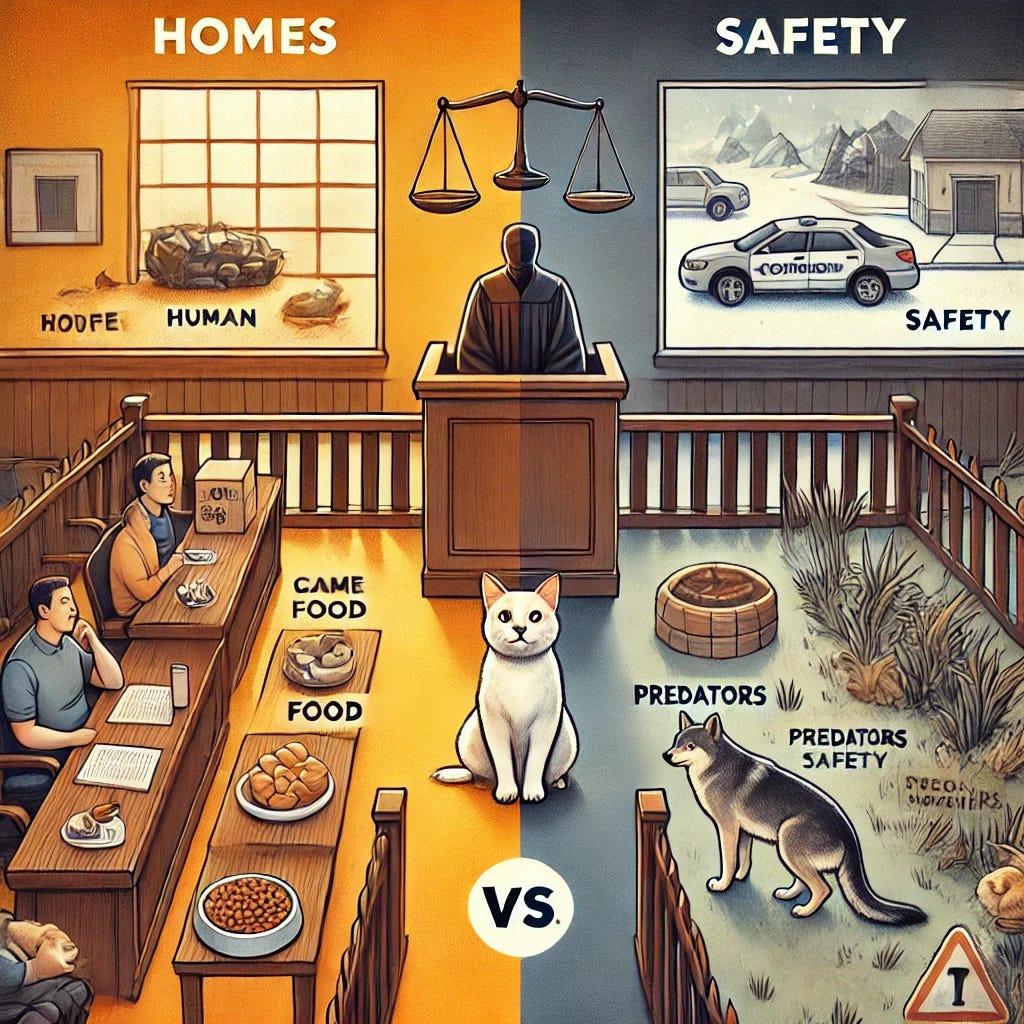

The case raises critical questions about how animal shelters should manage free-roaming cats and whether practices designed for feral cats should apply to friendly, adoptable animals. SDHS maintains that its CCP is a humane solution to overpopulation, but the plaintiffs argue that releasing friendly cats into potentially dangerous environments exposes them to harm, such as traffic accidents or predation by wildlife.

The case hinges on a critical distinction between feral and friendly, adoptable cats. Feral cats are typically unsocialized and unable to thrive in homes, making Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) a humane and effective solution for managing their populations. In contrast, friendly, adoptable cats are socialized and reliant on human care, with the potential to thrive in safe, loving homes. This distinction is at the heart of the plaintiffs' argument, as they contend that SDHS’s practice of treating these two groups identically under the Community Cat Program is both inappropriate and harmful.

Prosecution’s Focus: Protecting Friendly Cats

The prosecution's primary aim is to stop SDHS from releasing friendly, adoptable cats back into the community under the CCP. While Pease has clarified that he is not against Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) programs for feral cats, he argues that SDHS is improperly applying the same approach to friendly cats.

The case also raises questions about the broader impact on human communities. Beyond the risks to the cats themselves, the release of friendly, adoptable cats into neighborhoods could contribute to challenges such as nuisance behavior or health concerns. These potential consequences add another layer of urgency to the plaintiffs' argument, highlighting how the SDHS’s actions might affect both animal and public welfare.

Friendly Cats at Risk: Pease contends that friendly, socialized cats are being "re-abandoned" by SDHS under the guise of TNR. These cats, which could otherwise be placed in homes, are being released into environments where they face numerous dangers, including traffic accidents, exposure to predators like coyotes, and a lack of consistent food sources.

Violation of Animal Abandonment Laws: The plaintiffs argue that releasing friendly cats violates California’s animal abandonment laws, particularly Penal Code 597S. According to Pease, these socialized cats are dependent on humans and should not be treated like feral cats. By returning them to outdoor environments without ensuring they are cared for or adopted, SDHS is putting them at risk of suffering harm.

David and Goliath

In this case, the legal battle is not just about the fate of friendly cats—it’s also a classic David vs. Goliath struggle. On one side stands Bryan Pease, a nationally recognized civil rights and animal protection attorney known for his relentless advocacy on behalf of animals. Representing the Pet Assistance Foundation (PAF), Pease is taking on the well-resourced San Diego Humane Society (SDHS), which is backed by a formidable legal team from O’Melveny & Myers LLP, one of the largest and most prestigious law firms in the country.

With an army of high-profile attorneys, including Chris A. Hollinger and his colleagues, SDHS has significant legal firepower at its disposal. Yet, Pease, armed with his deep conviction and a track record of fighting for animal rights, is undeterred. This case represents more than just a legal battle—it’s a fight for transparency, accountability, and humane treatment for friendly cats across San Diego and beyond.

SDHS’s Defense: A Humane Solution for All Cats

SDHS, supported by expert witness Dr. Kate Hurley, a veterinarian and director of the UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program, defends the CCP as a humane, evidence-based approach to managing both feral and free-roaming cats. Since its launch in 2021, the program has served approximately 17,000 cats by providing veterinary care, sterilization, vaccinations, and other treatments before returning them to their outdoor environments. Dr. Hurley argues that this approach reduces shelter overcrowding and prevents unnecessary euthanasia by allowing healthy cats—both feral and friendly—to live successfully outdoors.

However, under cross-examination, she admitted there is no system to track these cats post-release, leaving their outcomes uncertain. In fact, this approach has led to disastrous consequences in communities nationwide, where released animals face dangers such as traffic accidents, predation by wildlife, and other harmful outcomes, while also creating public health and safety risks.

Feral vs. Friendly Cats: Dr. Hurley testified that while TNR programs were originally developed for feral cats, SDHS’s CCP includes all free-roaming cats. She emphasized that many of these adoptable cats are better off being returned to their outdoor environments after sterilization and vaccination rather than being kept in shelters where they may face euthanasia due to overcrowding.

Scientific Support: Dr. Hurley pointed to national studies showing that community cat programs reduce shelter intake and euthanasia rates over time. She argued that even friendly cats can thrive outdoors if returned to their original locations after sterilization.

However, during cross-examination by Pease, it became clear that there is controversy over this approach. Pease highlighted studies showing that some TNR-released cats were found dead or were repeatedly trapped and reprocessed—raising concerns about whether these programs truly benefit all cats.

Key Points of Contention

Friendly Cats vs. Feral Cats: The central issue in this case is whether SDHS should be releasing friendly, adoptable cats back into the community along with feral cats. While plaintiffs argue that these two groups should be treated differently—feral cats can be returned under TNR protocols but friendly cats should be placed in adoption programs—SDHS contends that its Community Cat Program (CCP) follows national best practices by improving outcomes for all free-roaming cats. The defense emphasized during closing arguments that none of the plaintiffs’ witnesses provided evidence of legal violations or harm caused by the program.

Risk of Harm: The prosecution argues that releasing friendly cats into outdoor environments subjects them to significant risks, including traffic accidents and predation by wildlife. They contend that these risks make it irresponsible for SDHS to release any socialized cat back into the community.

Monitoring and Accountability: Another key issue raised during the trial is whether SDHS adequately tracks what happens to community cats after they are released. Dr. Hurley admitted during testimony that there is no way to track individual cats once they are released because they are not microchipped or monitored. Plaintiffs argue that this lack of accountability makes it impossible to know whether these cats are thriving or suffering after release.

Weighing In: Supporting the Prosecution’s Position

As someone who has promoted and managed TNR programs for decades, I find myself aligned with the prosecution on this critical issue regarding the release of adoptable cats into potentially harmful environments. While I fully support TNR programs for managing feral cat populations, the idea of releasing socialized, adoptable animals into environments where they face significant risks is troubling.

Friendly cats depend on human care and protection; they are not equipped to navigate the dangers of outdoor life like their feral counterparts. When we release these animals back onto the streets without monitoring or ensuring their safety, we expose them to a host of dangers:

Traffic accidents

Predation by wildlife such as coyotes

Starvation due to lack of consistent food sources

Exposure to harsh weather conditions

These risks run counter to our mission as animal welfare advocates—to protect vulnerable animals from harm and ensure they have opportunities for safe, loving homes. I believe shelters like SDHS should make every effort to differentiate between feral and friendly cats when implementing TNR programs. Friendly, socialized animals deserve a chance at adoption—not abandonment disguised as managed intake to manipulate shelter populations.

Broader Implications for Animal Welfare

This case could have far-reaching implications for animal welfare programs across the country, particularly those involving community cat management. While TNR programs have been widely adopted as humane alternatives to euthanasia for feral cat populations, this trial highlights the challenges of applying such programs uniformly to all free-roaming cats.

Potential Changes in TNR Practices: If the plaintiffs succeed in their lawsuit, it could lead to stricter regulations on how shelters manage friendly or adoptable free-roaming cats within TNR programs. Shelters may be required to differentiate more clearly between feral and friendly animals and ensure that adoptable cats are placed in homes rather than returned outdoors.

Impact on Shelter Policies Nationwide: Animal welfare advocates are closely watching this case for its potential impact on shelter policies nationwide. A ruling against SDHS could prompt other shelters across the country to reevaluate their own community cat programs and consider changes in how they handle friendly versus feral animals.

Looking Ahead

With both sides having presented their closing arguments, we now await Judge Katherine Bacal’s ruling, which is scheduled for December 20 at 1:30 pm. The outcome could have significant implications for how shelters across the country manage community cats, especially in balancing humane treatment with public safety concerns.

Regardless of the verdict, this case highlights the urgent need for transparency and accountability in shelter practices—especially when it comes to protecting friendly, adoptable cats from unnecessary risks. While SDHS defends its Community Cat Program as a model for reducing shelter overcrowding, plaintiffs argue that releasing socialized animals into potentially dangerous environments is irresponsible. As this legal battle unfolds, I hope shelters will adopt more humane practices that ensure all cats are given the care they need to thrive in safe environments.

I will report on the Judge's decision and its implications following the December 20th ruling.

Ed Boks is a former Executive Director of the New York City, Los Angeles, and Maricopa County Animal Care & Control Departments, and a former Board Director of the National Animal Control Association. His work has been published in the LA Times, New York Times, Newsweek, Real Clear Policy, Sentient Media, and now on Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

I have heavily dove into this research. The research Hurley is using to support her statements is fraudulent in my opinion. Her main paper, “ Rethinking the Animal Shelter's Role in Free-Roaming Cat Management” is the cumulative basis for her position and it has significant flaws. First, she does not report a conflict of interest nor monetary influence, yet UC Davis Koret shelter medicine, which is her employer who is funded by Maddie’s Fund gives millions to support her million pet challenge and research. As you are aware I’m sure, Maddie’s also created and funds shelter animal counts database and changed their focus many times on how to get to no kill, which was then adopted and promoted by best friends who Maddie’s Fund also supports with millions each year. Second, the part of the research about the effectiveness and greatness of the CCP in the paper is sparsely cited and the citation that are listed are either from other researchers that Maddie’s fund gives money to, or Wolfe who is at Best Friends which is also funded by Maddie’s Fund. Thirdly, at least two of the citations used to quote statistics do not even have the statistic quoted in the original citation. It seems as if the percentage was made up in thin air because even looking at results data rawly one cannot come up with that statistic. Fourthly, she picked and chooses research that supported her position. Several studies out of the UK show that socialization level can be determined and that disease prevalence in a shelter drops if you provide cat rooms instead of cages. Hurley’s own research shows the disease prevalence is decreased if the cats are housed properly. Fifthly, she cites the national animal care and control association position paper which she was the sole contributor to, the ASV guidelines which her and Julie Levy penned (of note Levy is director of aU of Florida shelter medicine which Maddie’s fund gives millions to), and they use the data from shelter animal counts which as noted above Maddie’s Fund also gives millions too. The relationships are incestuous and is it really research or just smoke and mirrors. From someone with a doctorate who went through a problem based learning program where I had to rely on research and critically look at the methodology to learn, I would say this research is lower than a single case study which is bottom of the barrel in terms of evidence to show anything.

If anything, I would hope judge Bacal can see through all the “research” and see that it is nothing more than printed doctrine used to control the narrative.

Is this the same San Diego shelter that sent a huge transport of rabbits and guinea pigs to a rescue that was actually a reptile breeder? This is really sad.