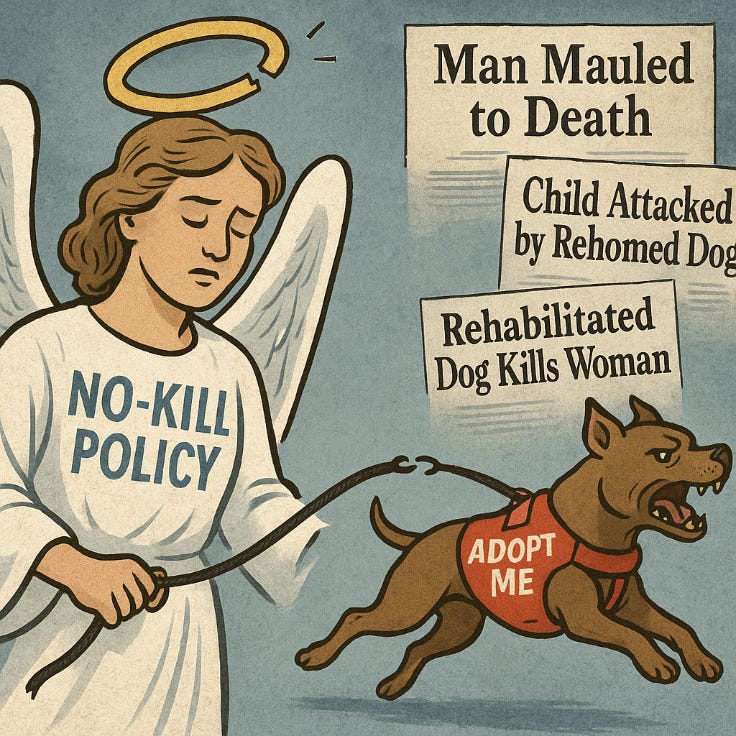

The Cost of Faux Compassion: When “No-Kill” Turns Deadly

Best Friends Animal Society Named in Wrongful Death Suit as Pattern of Fatal Attacks Raises National Alarm

The Detroit Tragedy: A Systemic Failure

On a frigid January evening in 2024, Harold Phillips was walking home from a Detroit bus stop when three pit bulls escaped through a broken gate and mauled him to death. The attack, horrific and senseless, was not the first involving these dogs. Neighbors had reported their aggression to Detroit Animal Care and Control (DACC) multiple times, and a child had been bitten years earlier. Yet the dogs remained with their owners, and no meaningful intervention occurred.

Now, in a groundbreaking wrongful death lawsuit, Phillips’ widow is not only suing the city but also naming Friends of Detroit Animal Care and Control (FoDACC) and, by association, Best Friends Animal Society (BFAS)—the nation’s most influential “no-kill” advocacy group—as parties whose influence shaped animal control’s response to repeated warnings and incidents.

The Limits of Influence: What the Lawsuit Alleges

It is important to clarify that there is no evidence that either BFAS or FoDACC directly managed the dogs or were involved in the specific decisions that led to Harold Phillips’ death. Rather, the lawsuit contends that BFAS’ partnership with FoDACC, and its national advocacy for “no-kill” sheltering models and high live-release rates, contributed to a policy environment at DACC where public safety concerns were sometimes subordinated to the pursuit of shelter metrics.

Systemic Pressures, Not Direct Causation

The Detroit case exemplifies a broader concern voiced by critics: that the drive for “no-kill” status—popularized and incentivized by organizations like BFAS—can create systemic pressures on local shelters. These pressures may encourage decisions that prioritize live-release rates over decisive action on dangerous animals. Critics argue that this dynamic is not unique to Detroit, but has played out in communities across the country where the pursuit of national benchmarks sometimes overshadows local public safety needs.

A National Pattern: When “No-Kill” Goes Wrong

The Detroit case is not an outlier. Across the country, a pattern has emerged in communities that have adopted the BFAS model: preventable fatalities, public safety crises, and animal welfare systems buckling under the weight of policies designed to boost shelter “live release” rates—regardless of real-world consequences.

In Los Angeles, a 13-year-old girl suffered life-altering injuries after being mauled by a pit bull adopted from a BFAS managed facility—a dog with a known bite history that was allegedly downplayed.

In Hidalgo County, Texas, a six-year-old girl’s face was torn off by a dog rehomed from a shelter operating under BFAS-aligned policies; the lawsuit alleges the shelter failed to disclose the animal’s behavioral record, potentially influenced by pressure to maintain its live release rate.

In Putnam County, Florida, a postal carrier was killed by dogs whose owner had previously tried to surrender them but was turned away by a shelter adhering to a “no-kill” managed intake model.

Upstream Prevention vs. Downstream Optics

For many, the term “no-kill” evokes compassion—an end to the euthanasia of healthy, adoptable animals. My own philosophy, shaped by decades in animal welfare leadership, emphasizes upstream, community-based solutions: intensive spay/neuter efforts, public education, and prevention strategies aimed at humanely reducing excess animal populations before they ever become a problem.

Measured by per capita intake and outcome rates, this approach treats euthanasia not as a shelter statistic to be managed, but as a symptom of deeper community failure. Targeted, mandatory spay/neuter programs remain the only proven method to address chronic overbreeding and abandonment. National data and lived experience confirm: prevention, not PR, is the path to lasting, humane outcomes.

BFAS has taken a different approach. Its “no-kill” model centers on downstream strategies: managed intake, community release, and mass animal transport—and a marked deprioritization of spay/neuter. These policies aim to reduce euthanasia on paper by limiting shelter admissions and relocating animals, but they fail to address the conditions that lead to overpopulation.

The distinction is critical. Where upstream models work to solve the crisis through prevention, BFAS’ methods merely shift or delay it—frequently at the expense of animal welfare and public safety. Their redefinition of “no-kill” has influenced a broader shift in the movement—from systemic reform to statistical cosmetics.

The Fundraising Feedback Loop

What once appeared to be a “conspiracy of dunces”—a mix of denial, intimidation, and misaligned incentives—now increasingly resembles a deliberate strategy. Public records, whistleblower testimony, and financial disclosures suggest that BFAS and its partners have built a fundraising model that depends on a perpetual crisis narrative. Dramatic rescues, urgent appeals, and emotionally charged messaging drive donations, even as the root causes of shelter crowding and dangerous dog incidents go unaddressed.

Critics and former insiders have noted that BFAS has redirected resources away from prevention and spay/neuter toward marketing and public relations. This shift keeps the crisis narrative alive—and the funding flowing—despite mounting evidence that the policies sustaining it are failing both animals and the public.

Introducing a Veteran Watchdog

As news broke that BFAS had been named a defendant in the Detroit wrongful death lawsuit, I turned to Merritt Clifton, publisher of Animals 24-7 and one of the nation’s most seasoned watchdogs of animal welfare policy. Clifton has tracked the evolution and consequences of sheltering strategies for decades, often warning of the unintended fallout from reform models that prioritize ideology over data.

Data, Not Dogma

Clifton is sometimes labeled by no-kill and pit bull advocacy groups as “anti-pit bull,” but this characterization obscures the foundation of his work. His perspective is rooted in decades of public data analysis and community safety reporting. While critics may dispute his conclusions, the facts he presents—regarding shelter intake, euthanasia rates, and severe bite incidents—are drawn from verifiable public records. Dismissing these findings as “rhetoric” deflects from the real question: what are the actual outcomes of the policies being implemented, and who bears the cost when they fail?

Unheeded Warnings, Documented Evidence

In a recent email to me, Clifton wrote, “I repeatedly warned all of the upper echelon at Best Friends between 2000 and 2013, in person, that they were setting up future fatalities.” He shared this perspective specifically in light of the Detroit case, underscoring that such outcomes were foreseeable—and, in his view, preventable.

He later provided his 2012 email exchange with then-CEO Gregory Castle, along with attack trend data showing a sharp rise in serious incidents during the rollout of BFAS’ downstream policy model. “After it [human fatalities] began happening,” he added, “Beth and I were obviously persona non grata.”

The comment suggests that as the consequences of BFAS policies materialized, the organization chose to distance itself from those raising alarm—rather than confront the emerging crisis. That same impulse may explain why current Executive Director Julie Castle declined to respond to questions for this article.

While the evidence does not suggest intent, it does raise important questions about accountability for the results of these policies. The lack of response from BFAS leadership leaves these questions unanswered and open to interpretation.

The Consortium and the National Stakes

BFAS does not act alone. It anchors a powerful network—dubbed “The Consortium”—that includes the ASPCA, Maddie’s Fund, and the UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program, among others. Together, these organizations have shaped national shelter policy, promoted metrics-focused models, and lobbied against transparency legislation, including California’s Bowie’s Law. The result, critics say, is a system increasingly centered on image management: shelters that turn away animals in crisis, communities coping with abandoned and dangerous pets, and a public too often kept in the dark.

Requests for Comment

Despite BFAS’ central role in shaping national shelter policy—and its recent inclusion in the Detroit lawsuit raising serious public safety and accountability concerns—Chief Executive Officer, Julie Castle did not respond to a request for comment. Animal Politics specifically inquired about BFAS’ policies, transparency, and the mounting criticisms surrounding its interpretation of “no-kill.” The silence is noted.

Animal Politics also reached out to Kristen Hassen—one of the nation’s most influential proponents of managed intake and “no-kill” sheltering strategies—for comment on the Detroit case, policy interpretation, and public safety concerns. Despite her extensive role advising jurisdictions on these matters, Hassen did not respond.

A Call for Accountability and Reform

The Detroit lawsuit is more than a local tragedy—it is a national inflection point. The evidence is mounting: when organizations prioritize downstream metrics and crisis-based fundraising over prevention, transparency, and safety, the consequences can be fatal.

It is time for the animal welfare movement to return to its roots in evidence-based, humane prevention—and to demand accountability from those shaping national policy.

For Harold Phillips—and for communities across the country—accountability is not just overdue; it is urgent.

Ed Boks is a former Executive Director of the New York City, City of Los Angeles, and Maricopa County Animal Care & Control Departments, and a former Board Director of the National Animal Control Association. His work has been published in the LA Times, New York Times, Newsweek, Real Clear Policy, Sentient Media, and now on Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

Stay Informed

For more analysis and updates on the evolving landscape of animal welfare policy, visit Animal Politics with Ed Boks.

You're describing a loss of common sense.

This article misrepresents the No Kill movement by framing preventable tragedies as unique to it, when such incidents occur in all types of shelters — traditional, high-kill, and No Kill alike. The false premise is that these are No Kill-specific failures. They are not.

No Kill’s core principle is to save every healthy and treatable pet, including those with medical or behavioral needs that can be rehabilitated. It does not reject euthanasia, but defines it properly: the merciful end for animals who are truly suffering and beyond help. What it rejects is killing for space, convenience, or manageable conditions.

Behavioral prediction is an industry-wide challenge, not a No Kill flaw. Traditional shelters have long used discredited behavior tests to justify unnecessary killing. Blaming No Kill while ignoring this broader context is misleading.

It’s also irresponsible to single out “pit bulls” in one example, while referring to “dogs” elsewhere. That reinforces harmful stereotypes disproven by science and undermines fair treatment for all breeds.

The No Kill Equation offers a proven, ethical, and data-supported framework. When failures happen due to poor execution, the blame lies with management, not the philosophy.

If we're judging shelters by their worst outcomes, let’s look at those still killing healthy, treatable animals every day. No Kill is the only model that challenges the status quo and demands better.

Let’s avoid gross generalizations about the most successful reform of shelter practices ignited by the No Kill Movement. Let’s support science, reform, and the belief that every life counts.